I

In a world plagued by deception, we often find ourselves wondering if there is something that we are not being told, some secret kept from us by an occult power. Those who keep speaking of a world of conspiracies claim that what we need is directness, certainty, and plain talk. This applies to everything, from religion to politics, from schooling to shopping, from art to entertainment. Somehow, those who “say it as it is” are preferred to those who care to remind us of our fallibility and how only by embracing our fragility could we ever come together to build a better world.

In a world of “straight talk”, we are expected to unquestionably consume what is expediently presented, hardly realizing that if we were to measure consumption with the same suspicion, we would find ourselves in complete paralysis. Just as in every department store, in the marketplace of opinion the claim is that everything is mired by doubt and wokery, and that happiness and reassurance could only come from certainty and plain truth.

Alas, when we realize that lies don’t hail from the “deep state”, but actually result from the false dogma of certainty and the yarns spun by “common sense”, it is far too late to push back on the predicament of tyranny.

II

Whether the promise of assurance is temporal or heavenly, whether found in a can of soda or in eternal life, what we are made to consume by way of presumed truth has to be received without question. The reason given is that truth is simple, commonsensical and direct. We are even schooled into thinking that questioning truth will result in misery and poverty. The core reasoning behind meritocracy is not success, but the opposite. Meritocrats claim that those who fail can only blame themselves because, either they don’t get it, they are too lazy, or they have been deceived by an élite of critical and negative conspirators who taught them to question meritocracy itself.

One could say that the era of directness keeps coming back in cycles where everything that seems easily grasped, literal and unmediated is quickly consumed and validated, while anything that appears to cause uncertainty is deemed as subversive, woke and elitist. We live in an age where anything that comes across as indirect is viewed with mistrust and total disdain.

If there is a realm of human activity that has been characterized by this toing and froing between what appears too literal and too occult or hidden, it is art. For all manner of reason, artists are often accused of cheating, especially when their work is perceived and denounced as dense, too abstract or “easy”.

A century ago, many were scandalized by the avantgarde flogging bicycle wheels on a stool, childish-looking paintings, and signed urinals on plinths. Then we had sharks in formaldehyde, artists running around naked in galleries, and more recently a banana taped on the wall made the news for all the wrong reasons.

Intentionally I am singling out what caused enough controversy because they stick in everyone’s mind, and not just the self-proclaimed art “connoisseur”. Yet, not unlike Maurizio Cattelan’s infamous banana, is there for the wrong reason. What sticks to mind is a denunciation of art, and with that a disdain for art’s virtue of indirectness.

III

If the denunciation of art’s indirect forms is a long-held sport, it is not because it makes sense to ridicule or laugh at what we are told to denounce what is “not art”. Rather it is because what we often claim to want to be art is the comfort of the directness by which, we ultimately realise, we are being lied to. Art’s indirectness is not seen as a virtue because the way art is often fed to us (and by which we are schooled in it) is just like anything else: gratuitously immediate and direct. Anyone who refuses to accept simple and literal truth is banished from the polis.

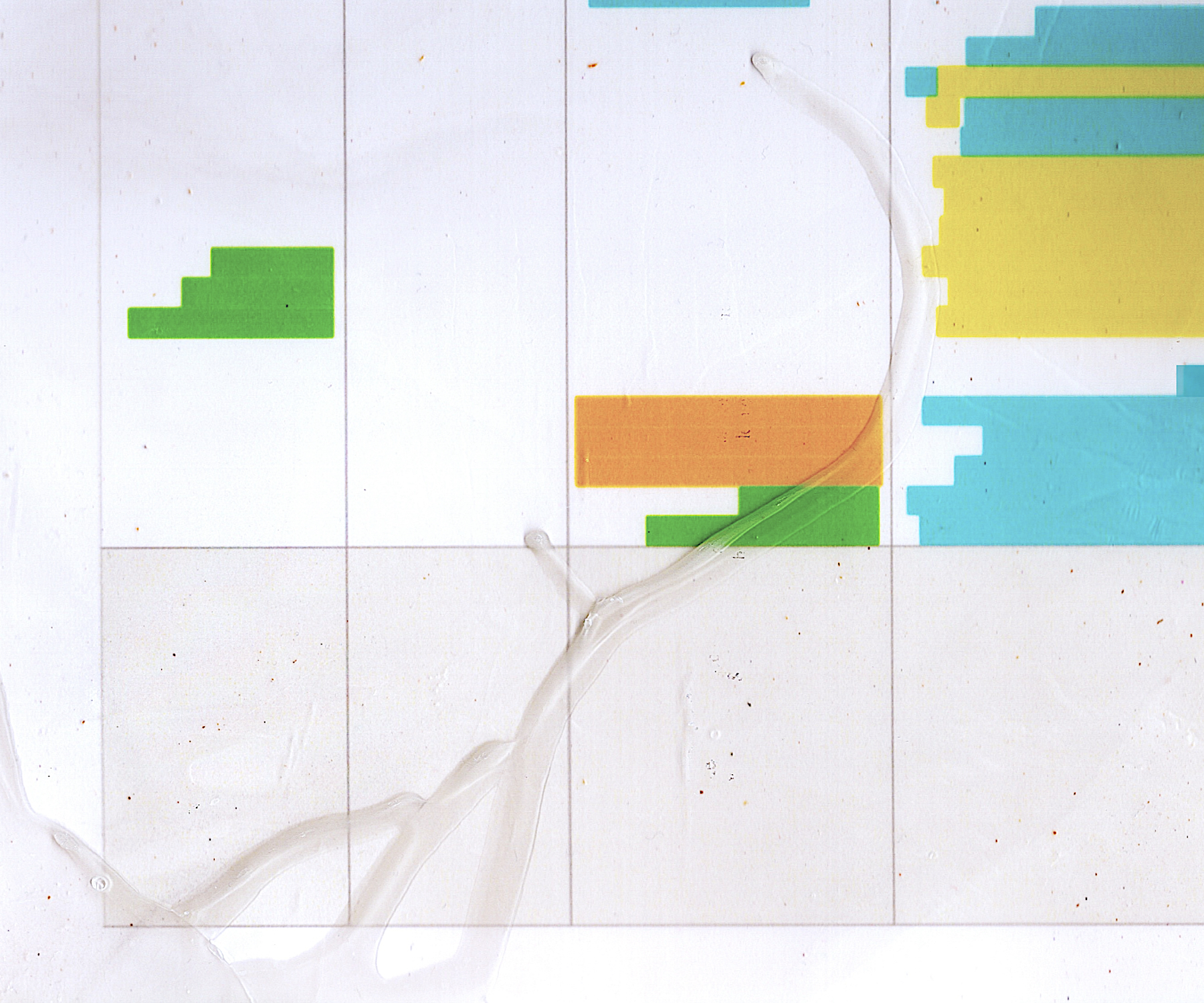

This is where I find in Henrjeta Mece’s work a strong iteration to counter the hegemony of directness. In this body of work, Mece is telling us to look and feel form as a ledger of indirectness. Her artwork invites us to challenge the immediate “needs” that are often imposed on anything we do. More so, Mece’s invitation to indirectness is not symbolic, but concrete. She is telling us to directly experience indirectness, thus speaking several times to the truth that art gives us.

This raises several issues for clarification. The first being that of form’s ledgers, the second concerns how indirectness is inherent in form itself, which then leads us to the rather complex, yet no less important case for art’s multiple iteration of truth, where we arrive at what art asserts, from more than one direction and iteration.

In its ledger form, Mece’s process becomes the work itself. It is doing away with artificial distinctions that are often made between form and content, process and product, presentation and meaning. Questions like “What does this mean?” become irrelevant because what Mece’s work is telling us is to move beyond the immediate need for art to mean something. Rather, Mece’s work suggests that the absence of what one seeks is the first indication that art’s meaning is neither direct nor should it be instantly gratifying. Somehow the suggestion is that there may well be several possible meanings but that is not what matters in one’s encounter with art.

This leads us to the second instance: that of indirectness as what inheres in art as form. Here the quibbling over form and content is also set aside, and instead we are invited to take on where the form frames us—thereby implying that the artwork by and in itself is a referent of what it is. The form is not simply the shape and the material that make the work, but the presence of it as a form, which leaves us wondering how and why the apparent lack of clear direction is telling us that perhaps, we need to open ourselves to the work and relate with what it may or may not signify, rather than simply mean.

Signifying more than one possibility implies several iterations. Unlike those who keep insisting that art should have a direct meaning and one take, here we are saying that actually art is a series of iterations, which may or may not happen in a set of instances, and where the possibilities of how, what and when this happens depends on us—us being the audience that participates in the art work’s own existence. In this respect, art’s truth is not one but multiple. This is suggested by empty ledgers whose possible meaning continuously return to us, just as we continuously go back to Mece’s work to figure out how best we can engage with it.

In recognition of the complexity of human intelligence, art is a means by which we come to truth in diverse assertions and attempts. Hence the indirectness of making and doing art comes in ledger form, which suggests not only a rubric or table, but also what becomes an archive that invites one to look for and engage in continuous search, research and re-search.

IV

Henrjeta Mece’s ledgers of indirectness are generous in how they make suggestions and how they give us possibilities through colour and occasional words to find one’s way into further promise and meaning—that is, the truths which the artist herself might not have even encountered, knowing well that this is where the audience partakes of the work, and where the work is sustained in its autonomy.

It is also in this autonomy that form is asserted and comes in its multiple iterations and truths – recalling what the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard regarded as the indirect communication by which we engage with the world, with each other, and more importantly to him, with God and in turn God with us. The intermediary roles played in this form of a shared and relayed sense of truth comes with huge promise, in that nothing is closed down to single forms of engagement, and where the possibility of new forms of communication keep emerging.

The claim made since the Enlightenment to freedom and intelligence as that which marks us as a rational species, cannot stop with what we quickly consume as a completed and exhaustive body of knowledge. This is where doing art reminds us that what we are and what we do begin with an awareness of the incompleteness and contingency from where we garner a sense of hope to seek continuously what we are not yet.

If directness wants us to assert art in its completed form, then we don’t need art. Instead, form is that by which art lets us explore what could never become to completion. This is where form’s ledgers are an index of what we are always invited to look for, while never given the impression that what will be found is to foreclose anything further. Which is also why, Mece’s work is a powerful reminder that through art we can do just about everything we want to do, if only to reject those who try to deceive us with their direct claims to the world’s truth.

JOHN BALDACCHINO is an essayist, visual artist and academic. He is Professor of Art and Education at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, USA. He specializes in art, philosophy, education and has written extensively about Mediterranean aesthetics. In addition to his papers and articles, he is the author of several books, including Easels of Utopia (1998/2018), Avant-Nostalgia (2002), Education Beyond Education (2009), Makings of the Sea (2010), Art’s Way Out (2012), John Dewey (2014), Art as Unlearning (2019) Educing Ivan Illich (2020), Lessons of Belonging (2023).

HENRJETA MECE is a cross-disciplinary artist, curator, and scholar. She is an AssistantProfessor, Teaching Stream in the Department of Social Justice Education, at University of Toronto. Mece holds a PhD from UofT and has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards. She is the founder of TriangleD Contemporary—a space for art, culture, and critical dialogue forthcoming in Toronto. Mece’s work draws on a variety of artistic practices such as, drawing, painting, and performance questioning the discourses of history and geography as languages in crisis and their play on production of identity and belonging. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at venues including, Palazzo Loredan, Venice (IT), Zweigstelle Berlin, Berlin (DE), MOCCA, Toronto (CA), and ISCP, New York (USA). Mece represented Central-Eastern Canada amongst 200 artists at the Great and North exhibition in Venice, and her work is part of Luciano Benetton’s world-wide Imago Mundi Collection.