The exhibition that Henrjeta Mece presents at YYZ is deceptively simple: a series of twenty pastel–colour-coded graphs presented singly on wall-mounted displays for easy ‘reading’. These displays start outside the entrance to the gallery, then snake around the entrance, through the glass windows, and into the gallery itself, culminating in a plinth topped with individual pieces of paper.

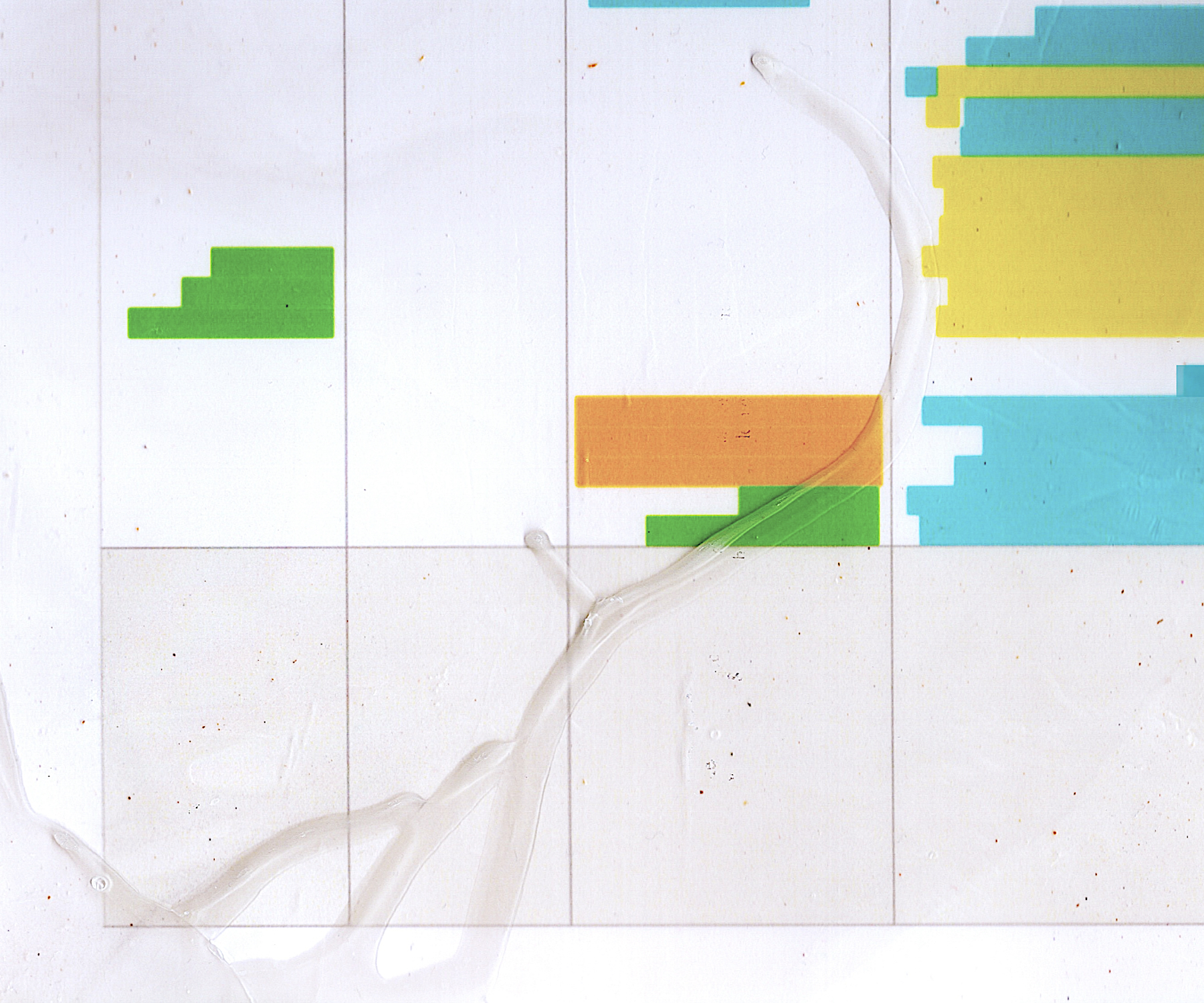

Other than a few headings denoting the various categories of data[i] collected, these graphs are mute, revealing no details of the tantalizing “profiles” Mece offers up. The viewer stands before them, comparing and contrasting the sizes of the colour blocks: participant A has a large block of education with a smaller block of artists’ residencies whereas Participant D has mostly graduate artists’ residencies, and so on. But ultimately, the graphs yield few specifics and we are left with our overall impressions of these objects themselves. Almost out of the corner of the eye, the viewer spots several bright red coloured blocks with text inside amongst the graphs. On reading these, the viewer comes to realize that Mece’s children have written notes to her randomly within her data collection graphs which she has left unchanged. (I mis you momy, Love from dodo to mama).

And this expands this project both outward and inward – into the world and back to the family. In speaking with Mece, she reveals that her twin children were 2 ½ years old when she began her doctoral journey and 4 ½ by the time she had begun to collect her data (gleaned from a number of interviews she did in order to complete her PhD in Social Justice Education and Diaspora and Transnational Studies at the University of Toronto in 2023). As she worked at her desk, the children would move closer to her until they were almost entwined with her body. Gradually, she came to understand that they were not interfering with her academic work – that, as a woman, a mother, and an artist, her children were contributing to it. As they lived with her research, they influenced her conclusions, leaving her little notes while learning how to spell as she laboured away on her dissertation.

Thus, she came to include the notes that they left for her in the graphs that comprise this exhibition, allowing their voices to emerge as integral to her. She acknowledges that having children has changed her concept of the future; that she is now more concerned with what she leaves behind in the world. And she is ever conscious of how difficult it is to find the right balance between her work as an artist/scientist and her role as a mother. Here it should be noted that each of the graph pages has been coated in wax, not expertly, but obviously by hand, with drips and blobs allowed to remain until solidified, lending an artisanal feel to the

In conversation with Mece in preparation for this essay, I learned that the graphs are based on data she garnered from the 2+ hour interviews she conducted with 10 well-known artists, arts administrators and arts faculty. These 700+-page interview transcripts were a key component of her PhD thesis resulting in a 300 page document (in the process of becoming a published book) and the artworks (graphs) included in this exhibition. Her research focused on artists’ residencies, theorizing that they are instrumental in contemporary arts education and in bridging the gap between the end of an individual’s education and their entry into their field of practice.

To produce the graphs, Mece used the data to generate themes and to organize the materials, highlighting the information in what she refers to as a “carnivalesque” manner. In an email exchange, she clarifies her work in relation to Mikhail Bahktin’s notion of the term:

“(…in my work) the carnivalesque refers to both the method and its end results – the artwork. As one of the methods used in the data analysis itself, it manifests the dissolution of hierarchical relationships between scientific research and art practice. Both of these fields are research-based fields of practices. This artistic method is initially used as a way of distinguishing the key information within the data by coding with colour the importance and relations within and between emerging themes. However, its distinct disorderly or, chaotic aesthetic takes a life of its own. In a way, the data table is the same other than, in the artwork pieces the text is now coloured the same colour as the highlights and the white background—it blends in. The text is still there just illegible or invisible to the eye.”

And what about the title of this enigmatic set of documents, The Scientist? Is this a work about a person who, in classical definition, “… is studying or has expert knowledge of one or more of the natural or physical sciences”? A latter-day Marie Curie perhaps? Or is Mece herself the scientist, the definition of which has expanded to include social scientist? She clarifies in this same email exchange, saying:

“(the …title) makes reference to me as both, a social scientist and an artist. This research is considered scientific and in the academic context, it was awarded with a Doctor of Philosophy which is a scientific title. Though I make the reference to the historic lab and studio isolated figures in all three contexts: the science scientist, social science scientist, and artist. The nature of inquiry and research commitment for these three roles is similar in nature whereas the methodology and methods might be different. Devoting years at a time to a work project, while immersed in human commitments, relationships and family are almost never foreseen in the initial consideration.”

Mece has said that the aim of the exhibition was to link the work of scientists in their labs to artists in their studios, and in the process to dispel the notion that each exists in the “ivory tower” of pure research. By including the insistent voices of her children (their notes to her) in the exhibition, she brings the reality of any mother/artist or mother/ scientist to the forefront. The purity is a myth. Dinner has to be made, noses wiped, skinned knees tended to – a million and one things that having children entails. And still the work must be done, the artistic and the scientific work, not outside of the children, but with them.

In The Scientist Mece is a collector and an arranger of data from which a theoretical discovery arises, with an aura of subjective objectivity and neutrality conferred by this title holding until…

Her children’s voices intervene, the only legible texts throughout the work, nonchalant yet somehow urgent: hugs…kisses…I love you mommy…I LOVE YOU MOMMY. Their persistence endures, washing over all the other data, like waves on the shore, lapping at the sand…over and over.

[i] Categories include: Demography, Interviewee, Education Experience, Artist Residency Experience, Variety of Residencies, On Contemporary Art Education, Decolonization Artists’ Residencies and Art Education, Contrasting Graduate Artists’ Residencies with Graduate School.

overall exhibition. But it is this wax coating that will act as a preservative for the pages, eternally saving the notes from the children. Mece thinks of wax as a warm, organic, skin-like covering, saving not just the data, but the voices of her children.

LISA STEELE is a Professor Emerita at John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design. Steele works in video, photography, film and performance as well as writing and curating on video and media arts. Steele and Kim Tomczak have exclusively collaborated to create videotapes, performances, and photo/text works since 1983. Steele’s videotapes have been extensively exhibited nationally and internationally including: at the Venice Biennale in 1980, the Kunsthalle in Basel, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the National Gallery of Canada, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Long Beach Museum. Her videotapes are in many collections including The National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Houston, Texas, Ingrid Oppenheim, Concordia University in Montreal, Newcastle Polytechnic in England, Paulo Cardazzo in Milan, the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo, the Akademie der Kunst in Berlin, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.

HENRJETA MECE is a cross-disciplinary artist, curator, and scholar. She is an Assistant Professor, Teaching Stream in the Department of Social Justice Education, at University of Toronto. Mece holds a PhD from UofT and has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards. She is the founder of TriangleD Contemporary—a space for art, culture, and critical dialogue forthcoming in Toronto. Mece’s work draws on a variety of artistic practices such as, drawing, painting, and performance questioning the discourses of history and geography as languages in crisis and their play on production of identity and belonging. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally at venues including, Palazzo Loredan, Venice (IT), Zweigstelle Berlin, Berlin (DE), MOCCA, Toronto (CA), and ISCP, New York (USA). Mece represented Central-Eastern Canada amongst 200 artists at the Great and North exhibition in Venice, and her work is part of Luciano Benetton’s world-wide Imago Mundi Collection.