In a conversation, David Court said to me that since he submitted a proposal to YYZ’s generic call, he was in some way inviting himself rather than adapting his practice to a given framework, which usually characterizes site-specific “interventions”.[1] However in turn, he asked me to write an introduction to his show and thus “imposed” my response to an institution, bypassing the selection committees of peers that otherwise predicates the selection of content in an artist-run center. Additionally, this text was written without me having been able to see many of Court’s exhibitions, and therefore it is largely the result of distilled documentation, transformed as it were it into a fiction of primary experience.[2] During our conversations, Court and myself talked about the vicariousness of language in art historical essays, when an author gives a belated second chance (a deferred reception) to the often nearly imperceptible gestures that made some artworks often blend completely into their surroundings. Notwithstanding the fact that the artist could himself offer this narrative, there is still the remaining necessity to graph other prosthetic discursive entities to his speech for means of legitimation. Moreover, even when there is commonality between cultural producers (usually transpiring from an artist-run center ethos), the polarization of the invitation and the response prevails, shifting an unintelligible collective will towards the individual artist, and his scribe, becoming, à deux, a “subject supposed to know.” In other words, they are asked to answer to social situations under the rubrics of proper names, accruing their capital, symbolic or otherwise.

In the last few years, Court ‘s exhibitions have seemed to approach the question of responsiveness away from the presupposition that his role (and that of his collaborators) would be above all to “reveal,” once more, hidden meaning unspeakable by the institution hosting the work. In a sequence of projects begun in 2012, he has focused instead on the way another kind of consideration of context could address ghostly things “hidden in plain sight.” As an example, Court has engaged with the phenomenology of visible dissimulation by making an allegory out of the infrastructure of the “green screen” technique, allowing video editors to juxtapose incompatible segments of reality within a unified and continuous visual field.

In this exhibition at YYZ, David Court reformats materials from his previous show, Artist’s Rendering (Distressed, Relaxed), presented at the artist-run center AXENÉO7 (Gatineau) in March and April 2017. At the time of writing this text (August 2017), he had not yet decided which of the components of the previous display would reappear[3]. Located in a former industrial area of Gatineau, AXENÉO7 occupies a converted textile mill, the Hanson Hosiery, which is part of a larger industrial complex, at this point largely recycled into other uses. For the show, Court incorporated the recent outcomes of a familiar debate on art and gentrification, but he also attempted to slightly change its terms. He lived for many years in Brooklyn, New York, and more recently, in Columbus, Ohio, where he witnessed different forms of urban change under late capitalism. It has become a leitmotif to say that the arrival of artists and the so-called “creative class” in overlooked neighborhoods increases the value of properties, pushing the poorest populations to the periphery. Eventually, these artists are themselves evicted from the enclaves that had welcomed them, and they have to migrate to other parts of cities. The cycle continues until urban living becomes unbearable for all, except the wealthy[4]. Through our participation in the reproduction of this system, we always leave a footprint and conversely make space more and more abstract, to the point that some dwellings remain empty while their value on the market increases. Although the AXENÉO7 building as it is known today was inaugurated in 2002, artists had been occupying the premises since 1982[5]. In the vicinity there are some vacant lots, a few apartments and suburban homes. Nevertheless, unlike other refurbished industrial districts in Canadian cities, especially Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, this section of Gatineau won’t soon be the prey to a real estate boom going overboard.

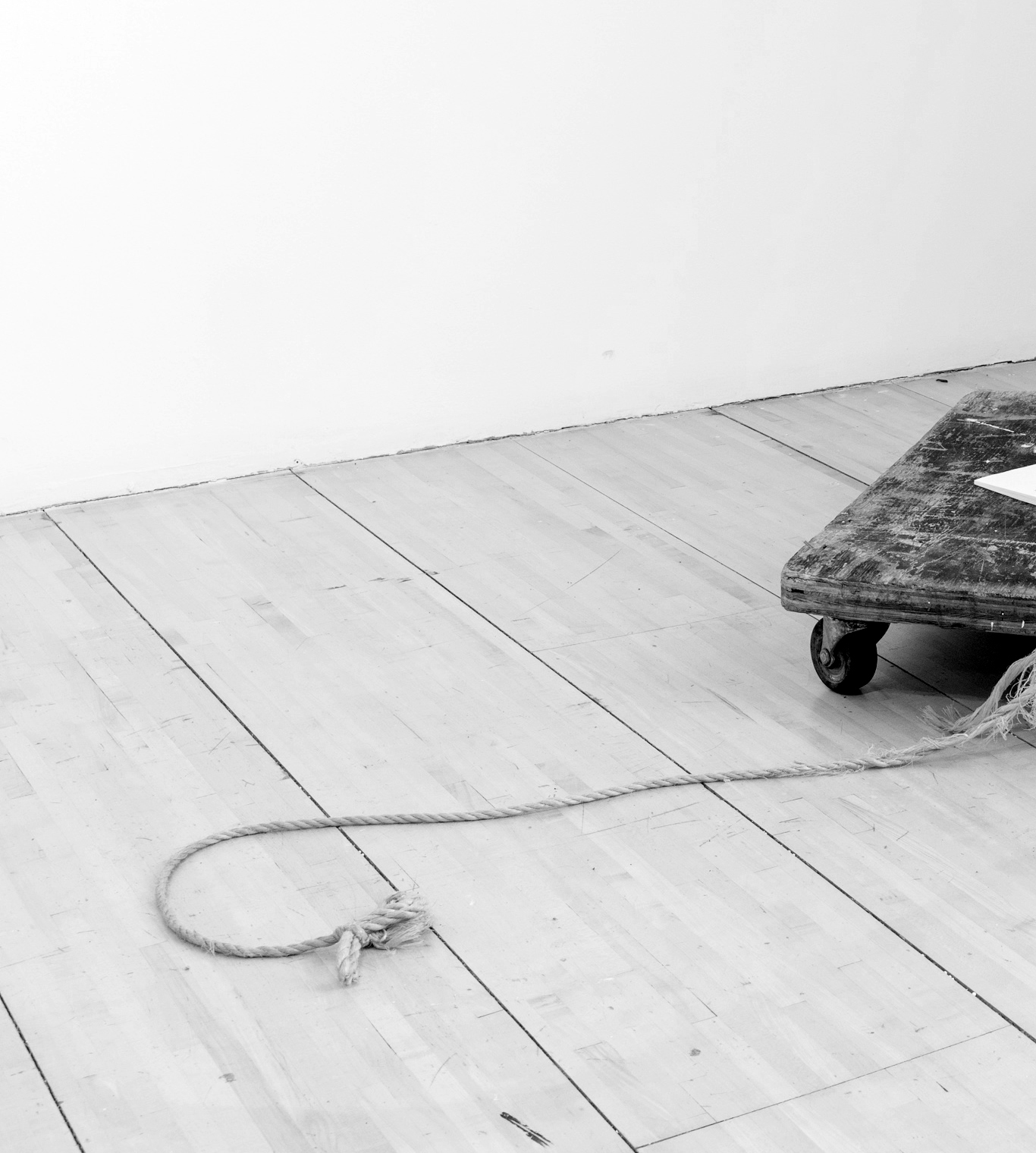

Overall, in the exhibition at AXENÉO7, Court established an abridged sequence in which each discreet element seemingly carried the potential to act as a trigger for pursuing a debate, in the fashion of institutional critique. Playing their own roles in this scenario, the staff could have used the content of the show to enact micro-performances, filing gaps in the knowledge of working class history of the neighborhood, and, at the same time, relay their own contemporary struggles as cultural workers. However the “discussion island” was not offered. As his notes, published on the premises, made clear, Court wished to avoid programing symbolic reparation, in which, ultimately, antagonisms are absorbed in a new dialectical synthesis.[6] He rather chose the path of obfuscation, distributing layers of observed misrecognition. Court has in common with several artists today that he leaves the fragility of meaning uncovered, instead of overly protecting it. The precariousness of working conditions extends to everything that is exposed in this setting, including himself. He understands that it is also vain to attempt to arrest the vast movement of digital dispersion which makes an image say a thing and its opposite, according to the hands that take hold of it. Court, however, works in the field of discourse, which asks for discriminating gestures. As he did in other projects[7], at AXENÉO7, he wrote this aforementioned statement establishing the limits of his agency, and he interpolated a bibliographical object in the epicenter of the exhibition, assembling into a precise constellation several excerpts of books and shorter essays consulted during the design and production of the exhibition.[8] This object did not occupy the paratextual place usually reserved for cultural mediation. Instead of making copies of the booklet accessible at the entrance hall table, Court “abandoned” them on an old dolly salvaged from an exhibition he participated in at Modern Fuel, Kingston in 2016 (with the artists Aryen Hoekstra, David Court and Shane Krepakevich). Nearby, he carefully positioned other “objets trouvés” (which he calls “unemployed forms” in the checklist): an antique loom shuttle and a wooden crate. On the walls, Court hung four prints encased in recycled wooden frames. For one, he made a montage out of images (found on Etsy) of a piece of loom (Reclaimed #1 (This/That)). For another, he retrieved a photographic print from the collection of the Beacon NY Historical Society, showing the former site of the Dia Beacon with heavy industrial machinery (Reclaimed #2a (A gallery that was once a factory)). In a fourth, he isolated a detail of the model of the refurbished site by the architects Rice and Lipka (Reclaimed #2b (Fabrication)).

The disused quality of the frames, the antique shuttle loom and the dolly seemed to displace with irony the fiction of use value in recent artworks salvaging techniques like weaving, mainly for the purpose of arresting “eye balls” on social media. This work was thus highly “instagrammable” against the grain, and at the same time, it referred critically to a larger phenomenon of cosmetic visuality : the tendency, since the late 1980s, to retain some of the patrimonial architectural detail of a converted industrial site as decoration. More than kitsch nostalgia, these encased features produce photo-ready cuteness[9] in a space where, for example, the body of museum visitors as well as tenants or owners of condos became monetized, interchangeable units. The renovation of the spinning mill at AXENÉO7 seems to have resulted from a compromise between the construction of “neutral” white cubes for artists and the valorization of the industrial/picturesque characteristics of the site. From outside, the letters spelling “Hanson Hosiery Mills” on the façade have been kept intact. Their towering presence could generate confusion as to what is the current function of the place inside for the passerby unfamiliar with the artist-run center’s mandate. Entering the first gallery, the project room where Court had his show, the viewer notices that one wall is interrupted by a large, perfectly square window, revealing the garden. Some artists choose to veil it with a curtain, but Court left it as it was, so that this landscape became the figure, almost eclipsing the ground. In the exhibition at AXENÉO7 all content thus blended in their surroundings by virtue of the integrative potential of the architecture. Opposite this window, Court screened a video on the most cutting-edge flat screen monitor, decomposing the contents of an engraving attributed to Thomas Morgan representing two luddites in a factory, destroying a loom. The visitor alternately saw the arms of the luddites, and the texture of a sample of fabrics filmed in close-up.

While attempting to give an afterlife to the ghost of Ned Ludd in the contemporary period, Court seemed to ask the question: is it still possible to throw the sabot in the machine while it is running? He knows that the answer to this question cannot itself emerge from the rehabilitation of iconoclastic gestures or falling into the negative of intentionality (eg. the so-called creativity of destruction). It must also integrate another kind of sabotage in the absence of direct human intervention: accidents, abstract protocols, or natural and economic catastrophe, generating their own forms and responses. Taking into account this contingency, during the process of writing this essay, I also wondered what was the embedded performance of avoidance in the repetition of the term “ambivalence” (which Court uses in his statements). As it is almost forcing a speech act on un-felicitous circumstances, does it allude to the impossibility of taking a stance (in the psychoanalytic sense of the split subject), or rather to the difficulty of finding one’s own respite (or semblance of autonomy) facing the current political situation, when others, less privileged, are pushed into the void? At the beginning of his famous text “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia,” Roger Caillois included the phrase: “Beware: whoever pretends to be a ghost will eventually turn into one.”[10] The meaning of his statement can be diverted to say that it is naïve, even dangerous, to hide behind the specters of anarchy when there is an urgency to patch broken social links in the present. Rehearsing the theatrical tropes of disappearing acts once more with feelings, saying again and again “I prefer not to,” risks letting unwelcomed forces occupy the place we have vacated. Here, I am using the plural but talking about my own doubts, and not parroting the artist’s, although we might agree on this.

[1] I had sent Court quotes from Jacques Derrida about the ontological status of the invitation and the response (in the philosopher’s case, embedded in an academic framework), which I thought would fit into a discussion gravitating around context in the art field as a given, even after more than 40 years of debates around site specificity. See Jacques Derrida, Passions (Paris: Galilée, 1993).

[2] What name do we give to this division of labour which produces a body of work, as well as the biography of an individual, from archival fragments? In disclosing this particular temporality of writing, and by extension, of art producing, one might say that the profiles of two readers of this text are hollowed out. The first one would have seen the works in the gallery, and would read this text during or after his visit. The second one would find the page devoted to the exhibition on the YYZ Website, much later. There is, perhaps, a third reader, finding the printout in a pile of press releases or didactic material remaining of his visits to the 401 Richmond building, a few months after the exhibition had closed. I am addressing him now, in the tense that we call in French the “futur antérieur.” I imagine this reader as the usual neglectful viewer, distracted, indeed even indifferent, but then discovering this text after the fact and actually remembering what he saw.

[3] It is important to point out that, for Court, the exhibition is never considered as the uttermost limit of conception. He often shifts his projects during the brief period of the installation, which is not usually devoted to production.

[4] Although part of its content is now dated, Rosalyn Deutsche’s book Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), still remains in my opinion a key reference on art and gentrification, particularly at its nascent phase. For an updated version of a debate about site specificity “increasingly assimilated into the capitalist logic of regeneration and value creation,” see When Site Lost the Plot, edited by Robin Mackay (Falmouth: Urbanomic , 2015).

[5] See the Website of La filature, a production center adjacent to AXENÉO7 serving the same community of artists : http://www.lafilature.qc.ca/histoire.html

(consulted August 31, 2017).

[6] David Court, “Notes on Artist’s Rendering (Distressed, Relaxed)”, 2017.

[7] For his exhibition Self-Titled (Materials for a 21st Century Room-SWAMPED, EXHAUSTED, HESITATING) at the gallery 8 Eleven, Court invited the poet Corina Copp to compose a text in response to the materials and references he was gathering for the exhibition.

[8] The texts are by Robert Binghurst, Muriel Combes, Claire Fontaine, Lewis Mumford, Sianne Ngai, Martha Rosler, Gertrude Stein, Bernard Stiegler and “others.”

[9] I use the term cute here in the way theorist Sianne Ngai repurposes it for cultural critique. She says: “Cuteness, an adoration of the commodity in which I want to be intimate with or physically close to it as possible, thus has a certain utopian edge, speaking to a desire to inhabit a concrete qualitative world of use as opposed to one of abstract exchange. There is thus a sense in which the fetishism of cuteness is as much a way of resisting the logic of commodification – predicated on the idea of the “absolute commensurability of everything”-as it is a symptomatic reflection of it.” Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories : Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge Massachusetts and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2012), p. 12-13.

[10] Author’s translation. It is quoted in French in the English version of the text as: “Prends garde: à jouer au fantôme, on le devient.” Roger Caillois, “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia,” October, Vol. 31 (Winter 1984), p. 16.

VINCENT BONIN lives and works in Montreal. Notable among his credits as a curator is the project Documentary Protocols (1967‐1975), presented at Concordia University Leonard and the Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery and composed of two exhibitions (2007-2008) and a publication (2010) exploring the development of artists’ collectives and self-managed associations in Canada during the 1960s and 1970s. He served as co-curator (with Grant Arnold, Catherine Crowston, Barbara Fischer, Michèle Thériault and Jayne Wark) of Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada (1965-1980), which travelled throughout Canada between 2010 and 2013. In collaboration with the curator Catherine J. Morris he organized an exhibition on the American critic Lucy R. Lippard entitled Materializing ‘Six Years’: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art, which was presented at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum in 2012-2013 (with a catalogue published by MIT Press, Cambridge). In 2013-2014, he conceived the two-installment exhibition D’un discours qui ne serait pas du semblant/Actors, Networks, Theories, held at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery and at the artist-run centre Dazibao, in Montreal, which examined the way “French Theory” was assimilated in Anglophone art milieus (the book following this exhibition will be published by Black Dog, London, in the Fall of 2017). In 2016, he curated Réponse, an exhibition responding to the work of the French philosopher Catherine Malabou, which was presented at the Musée d’art contemporain des Laurentides, Saint-Jérôme.

DAVID COURT is an artist and writer currently living and working in Ulster County, New York. He holds a Masters in Visual Studies from the University of Toronto (2009) and a BFA from NSCAD University (2006). Recent exhibitions include: Artist’s Rendering (Distressed, Relaxed), AxeNéo7, Gatineau, Quebec, 2017; You can tell that I’m alive and well because I weep continuously, The Knockdown Center, Queens, New York, 2017; Apparatus for a Utopian Image, Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts Project Space, New York, New York, 2016; Self-Titled (Materials for a 21st Century Room—or SWAMPED, EXHAUSTED, HESITATING), 8eleven, Toronto, Ontario, 2016; David Court, Aryen Hoekstra, Shane Krepakevich, Modern Fuel Artist Run Center, Kingston, Ontario, 2016.