Technical Points of Entry = Between Time + Space (All our wonder, unavenged)

Location / ~120,000 light-years wide spiral galaxy with a bar-shaped flat disk core / ~27,000 light-years from the center / On one of the four spiral arms / On mid-edge / Yellow dwarf star / Third planet from interior / One celestial body / Spaceship probe notes /

There was once a bipedal species unique to this planet. They were somewhat intelligent. They had the ability to communicate. They named things. They named themselves. In this case, they based their name upon their physical bodies in contrast to other living organisms. They called themselves human beings. We know this and many other details about their species because, as our records show, they were oddly self-reflective creatures. This ruminative quality may have been caused by their obsession with tracking the phenomenon they called time. Tracking time caused all sorts of interesting pathways for them to interact with their planet and each other. They based their passage of time on what they called a year, which was one revolution around their star. One granular level below this year was something they called a day, or simply put, one revolution their planet took to turn around. One year was equivalent to a full 365 days.

They also named the geological movements of the planets’ “eras”. During the early period of one of these eras, which they described as the Anthropocene, a novel coronavirus caused a global pandemic. The humans documented their species-wide crisis in detail. They said it occurred in the early 2020s. This is odd since our geological data shows that this planet was much older than 2000 so-called years—approximately 5 billion years older. Moreover, humans had in fact evolved for millennia before this moment in time. Throughout their existence, humans were quite industrious. Not only did they obsess about time, but they made things to capture their understanding of it. They created things in their own image. They created words for things they saw like “plants”, “birds”, “language”, “apples”, “oranges”, and a thing called “baseball”. They even created things to reflect their own images to each other in what they called “real-time”. They called this particular thing “Zoom”. It was during that aforementioned pandemic, specifically within their fourth wave of infections, in an area that they called North America, two humans communicated over this “Zoom” to share their mutual appreciation for connecting other humans on the matter-of-fact subject of making things for one another. Other humans gave this making-of-things a name, too. They called it “art”. Now, let us review their exchange, recorded from the perspective of one human speaking about the other human’s art.

Technical Points of Entry = The Aesthetics of the Two Things (Videos: Anyder + Campfire) + Human Creator (Claire Scherzinger)

Text example: Exhibition summary featuring brief transcribed quotes from two humans / Excerpt 1.1

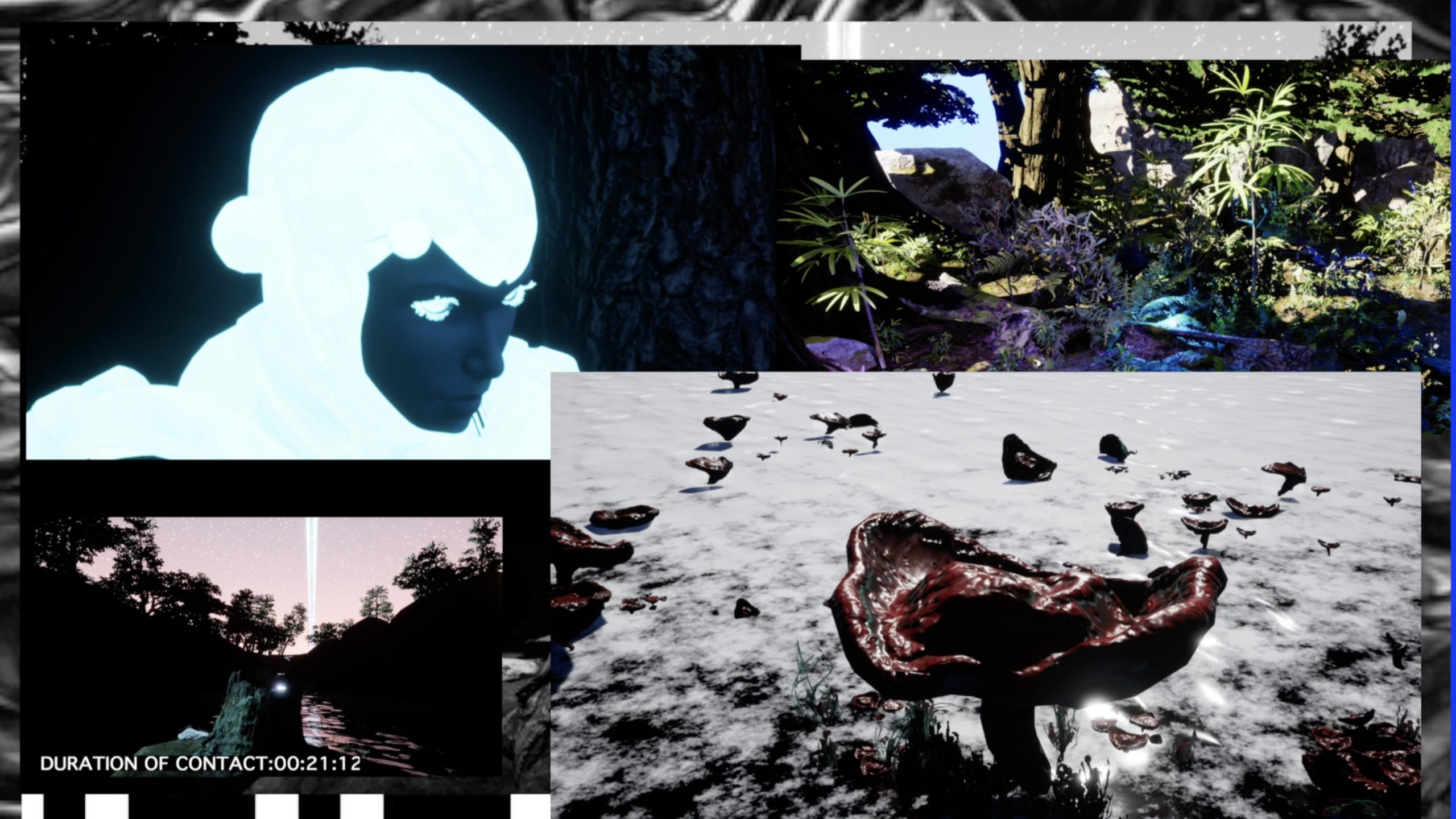

All our wonder, unavenged is the culmination of a digital visual expression by the Seattle-based Canadian-American artist Claire Scherzinger. The exhibition features two videos, Anyder and Campfire, both of which clock in at 40 minutes apiece. In their own unique ways, the videos are meditative narratives on how future or advanced beings, like ourselves, may explore familiar yet alienating landscapes that expand over solar systems and their geological eras.

Both videos exist in a kind of celestial orbit. Much like planets circling a star, Anyder and Campfire both rotate around an unidentified center. In tandem, they are a slow-burning and sincere investigation on how we cope with a finite understanding of abstract concepts like space and time. Scherzinger grounds this exhibition in a common, albeit appropriately conflated, soft science fiction visual language. With an acute understanding of the human condition that exists somewhere between wonder and terror, these artworks are balancing on a three-point threshold. Visually, the spaces occupied in the videos can be broken into three parts: The Above, in the void of space; The Below, in chasms, ravines, and flickering Day-Glo forests; and The In-between, through ethereal gaseous skylines. This trifecta is perhaps Sherzinger’s nod to a particular influence, Cixin Liu’s novel Dark Forest, a fictional response to the Fermi Paradox and itself a sequel to the novel The Three-Body Problem. In both works, humanity grapples with the existential dread of navigating space and time, and herewith All our wonder, unavenged invites us into a sensory delight to explore these phenomena.

To understand Scherzinger’s aesthetic choices of digital mediation as a mechanism to probe the potential of how we could (maybe) explore planets, we appropriately connect over zoom after the hottest summer ever on Earth’s record.

“Tell me about the software you used.”

[Human answering question breathes heavily]

“I don’t usually talk about how the sauce gets made,” Claire answers. “I’m always working from some source.” She pauses and continues, “The flora comes from what I’m seeing on hikes or growing in the garden.”

There is some truth to what she’s divulging. Many artists with a background in painting rather leave that slippage between what-am-I-looking-at and how-did-this-get-made the unknown. The traditional canvas is a point of play for the viewer to muse on. Rarely do we know what the tricks are and how they are employed with acrylic or oil. We only see the final result, pristine interpretations on larger themes on a physical object: a screen, a scrim, or a canvas. By showing many slow-moving screens at once, Scherzinger’s video works acknowledge that paintings are merely held together by flimsy physical materials and that over time, these painted images will decay, not unlike our bodies.

In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Philip K. Dick referred to this man-made object decay as kipple. “The First Law of Kipple,” he writes, “[is that] kipple drives out nonkipple.” Yet did Dick ever consider what would happen if kipple existed virtually? How would kipple embed itself into the stages of the artificial digital creation? How would this decay then influence a digital reflection on capturing a sublime unknown? All our wonder, unavenged is Scherzinger’s opportunity to acknowledge her foundational training as an object-maker, a painter, and to transpose those skills into a digital practice. An integral element of Scherzinger’s project, therefore, is letting the kipple join in the process. Much like Dick’s exploration of kipple, Anyder and Campfire acknowledge that “No one can win against kipple… except temporarily and maybe in one spot.” Planets are in different stages of life and decay. Rocks are in different stages of formation, water moving at different speeds. Rather than letting the viewer fall into a melancholic state, knowing that at some unfathomable time in the future the 2nd law of thermodynamics will take its entropic hold over the planet, Scherzinger creates that one spot for us to point up to the sky and stand firm to ask, Where can we go?

So what’s the starting point for Scherzinger’s aesthetic decisions that create the “rocket fuel” for this voyage? She asks us to exist, momentarily, somewhere between the three decades that formed her sci-fi perspective. We’re invited into a contemporary 1990s aesthetic with its GeoCities-style architecture of layers and challenging typography. There are references to the mid-2000s in the stylized, psilocybin-induced CGI 3D animated models that expand, pan, and contract across the screen. And if the visuals are not enough, they’re centered by an audio score that is reminiscent of the sounds of early 2010s, as if the music of ambient artists like Emeralds or Burning Star Core were being played through a dying duo AA battery-charged tape deck. And yet, this conflation of aesthetic periods and media is not alienating. There is an anchoring element that makes these 3D models moving in and out of the frame seem familiar.

Technical Points of Entry = The Language of Collage + Two Things (Anyder + Campfire)

Text example: Exhibition summary featuring brief transcribed quotes from two humans / Excerpt 1.3 / Note to Reader: Excerpt 1.2 unintelligible

As Scherzinger is a contemporary artist known for her lush paintings of otherworldly landscapes, the next question seems appropriate:

“Claire, how did you move from traditional painting to a digital multimedia practice?”

“Within the realm of a digital artist, I was, to a degree, trying to replicate the worlds of my paintings. For a long time, paintings were about rendering and making things look realistic, or a place to discuss realism that I was comfortable with. Currently, I’m interested in exploring realism in the context of the limitations of digital technology. I am using these digital tools to look at visual space as exploration.”

Considering Scherzinger’s words, it’s clear that the aim is not just an exercise in sci-fi reverie. There is no interest in applauding the numerous behemoth American franchise films and their pop-cultural bubblegum look that exists only to make 3D modeling and artificial rendering more real. Rather, the aesthetic point of entry in her artworks is collage, but more specifically the limitations of the form. While being wholly foreign in content, the collage format appeals almost subconsciously to the viewer, appealing to an idea or memory that makes them say, “This seems like something I’ve seen before”. The familiarity is found in a blending of sci-fi with a tradition of landscape artists like Turner or Jon Martin who hope to capture the rapturous sublime.

Anyder and Campfire’s neon green typography is an important collage-style device used to destabilize our interpretation. Both employ a familiar yet illegible typeface, meant to make you wonder, Why is this here? The text exists as a console-style point of reference for unknown things. In Anyder, emoji-like circular objects rotate on the screen. Are they an allusion to planetary bodies moving at rapid-fire speed? Are they the byproduct of an interstellar craft monitoring and collecting visual data from outside the hull while looking for life? The ‘alien’ typeface is forefront, unavoidable in an incandescent shimmer that rolls over into something like a countdown. What is the culmination of this sequence? In Campfire, the typography takes the stage as a mid-ground layer. Are we supposed to see the text as a prophecy of doom in relation to the visual landscapes overlaid? Is the text fading into the background because language no longer exists in this space?

I ask, “Claire, why did you choose these typefaces?”

“I wanted to capture a typography that humans have tried to make as illegible as possible, but everything has a source”, she continues, “So I found open-source typefaces as an interesting place to explore unknowing, sharing, and probe othering.”

The layering of a forced unknown text against boxes, screens, and viewports to suggest other worlds creates a positive and negative space for reflection. This visual space between collaged boxes juxtaposed with type is not lacunary. Rather, this dark matter reminds us to look up towards the sky for the same period of time as these videos and ask: What will happen in between these gaps? What will grow in the next epoch, era, or entropic (Kippled) end? Again we have three points on a threshold: a three-body problem.

Technical Points of Colliding = All combined + An Attempt Into the Sublime + Human Creator (Claire Scherzinger)

Text example: Exhibition summary featuring brief transcribed quotes from two humans / Excerpt 2.0 / Note to Reader: Prior excerpts all unintelligible

I urge you to sit in the space. Listen, watch, and reflect. We make things to speak about other things, but do these things ever speak back? All our wonder, unavenged offers a space to consider this question.

“Claire, is there a way out of our planet? Will we wind up in the interior of a spaceship, or on a desolate vista of an inhabitable planet?”

[Laughter]

This is something that Scherzinger’s been thinking about for a long time. When studying under Kelly Richardson as an MFA candidate at the University of Victoria, this sublime question was at the forefront.

Indeed, All our wonder, unavenged asks of us all: How do we deal with such a huge fucking ineffable thing? Accordingly cool and with a meditative quality not dissimilar to the cadence of the audio in the videos, Claire responds:

“It gives me goosebumps. Makes my heartbeat. It’s a visceral reaction. It’s as close to being human to scale as possible.”

I inquire, “Honestly, what are these two artworks?”

“Portals into the understanding of things that don’t yet exist.”

I press further. “Please explain… I don’t follow.”

“Space travel. What will be our ansible way to experience the unknown… to make it happen? It gives me chills because it’s so exciting. It also surrenders me to despair.”

“Why?”

“I won’t ever see space outside of the sky. My existence is limited and I’ve been mourning this realization since we were both children.”

Technical Points of Conclusion = Things Are Made of Things (All our wonder, unavenged)

Leaving Location / ~120,000 light-years wide spiral galaxy with a bar-shaped flat disk core / ~27,000 light-years from the center / On one of the four spiral arms / On mid-edge / Yellow dwarf star / Third planet from interior / One celestial body / Spaceship probe notes /

We have immediately sent this record to the magistrates’ royal archives. We have put forth a recommendation for the committee to consider this package of human existence to be submitted and approved for posterity in the Canon of Things. We await the committee’s decision.

NOTES:

Liu, Cixin. The Dark Forest. Translated by Joel Martinsen. London: Head of Zeus, 2021. Originally published as 黑暗森林 (Chongqing: Chongqing Press, 2008).

Liu, Cixin. The Three-Body Problem. Translated by Ken Liu. London: Head of Zeus, 2021. Originally published as 三 体 (Chongqing: Chongqing Press, 2008).

Dick, Philip K.. Blade Runner: (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?). 1st Ballantine Books ed. New York City: Del Ray, 1982. p. 57.

Emeralds [Elliott, John; McGuire, Mark; Hauschildt, Steve]. Does It Look Like I’m Here? Editions Mego. ℗ 2010.

Burning Star Core [Yeh, C. Spencer; Lesniak, Jeremy; Shiflet, Mike; Beatty, Robert; Tremaine, Trevor]. Challenger. Hospital Productions. ℗ 2008.

Le Guin, Ursula K. Rocannon’s World. New York City: Ace Books, 1966. First appearance of the word. Definition: faster than light communications.

BRENDAN A. DE MONTIGNY is a multidisciplinary artist, communications strategist, cultural connector, and curator interested in intersections between hyperreal technologies, utopianism, and contemporary art. He co-founded and directed the Ottawa-based contemporary art gallery PDA Projects from 2014-2018. As a visual artist, de Montigny has exhibited drawings, performances, and Installations across Ontario, Quebec, and New York state. He was a finalist for the 2019 RBC Emerging Artist Award. De Montigny holds an MFA from the University of Ottawa, a BFA from Concordia University, and a DEC from Heritage College. His cultural communications practice has led him to collaborate with organizations like Artscape, DAÏMÔN, IMAX, Shopify, Masterpiece Studio, and the co-design transformative practice Coeuraj.

CLAIRE SCHERZINGER has a BFA in drawing and painting and creative writing from OCAD University and an MFA in interdisciplinary arts from the University of Victoria. Her work has appeared in exhibitions across Canada and internationally in the US and UK. She was a purchase prize winner of the 2015 Royal Bank of Canada funded Painting Competition and was a finalist for the Equitable Bank Emerging Digital Artist Award. Her work can be found in the permanent collections of both banks. Upcoming exhibitions include Slowly Moving Through, featured on Daata.art and Mississauga’s Art on Screens, as well as upcoming 2 group and solo exhibitions at Karsh Masson (2022) and the Varley Art Gallery in Markham, ON (2023). Scherzinger currently resides in the Pacific Northwest.